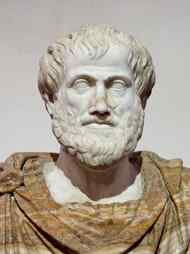

Aristotle

Aristotle, whose name means “the best purpose” in Ancient Greek,[7] was born in 384 BC in Stagira, Chalcidice, about 55 km (34 miles) east of modern-day Thessaloniki. His father Nicomachus was the personal physician to King Amyntas of Macedon. His mother, Phaestis, came from a wealthy family. They owned a sizable estate near the town of Chalcis on Euboea, the second-largest of the Greek Islands.

Life

Both of Aristotle’s parents died when he was about thirteen, and Proxenus of Atarneus became his guardian. Although little information about Aristotle’s childhood has survived, he probably spent some time within the Macedonian palace, making his first connections with the Macedonian monarchy. At the age of seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle moved to Athens to continue his education at Plato’s Academy. He probably experienced the Eleusinian Mysteries as he wrote when describing the sights one viewed at the Eleusinian Mysteries, “to experience is to learn” [παθείν μαθεĩν]. Aristotle remained in Athens for nearly twenty years before leaving in 348/47 BC.

Both of Aristotle’s parents died when he was about thirteen, and Proxenus of Atarneus became his guardian. Although little information about Aristotle’s childhood has survived, he probably spent some time within the Macedonian palace, making his first connections with the Macedonian monarchy. At the age of seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle moved to Athens to continue his education at Plato’s Academy. He probably experienced the Eleusinian Mysteries as he wrote when describing the sights one viewed at the Eleusinian Mysteries, “to experience is to learn” [παθείν μαθεĩν]. Aristotle remained in Athens for nearly twenty years before leaving in 348/47 BC.

His departure

The traditional story about his departure records that he was disappointed with the Academy’s direction after control passed to Plato’s nephew Speusippus. It is also possible that he feared the anti-Macedonian sentiments in Athens at that time and left before Plato died. Aristotle then accompanied Xenocrates to the court of his friend Hermias of Atarneus in Asia Minor.

In Lesbos

After the death of Hermias, Aristotle travelled with his pupil Theophrastus to the island of Lesbos. Together they researched the botany and zoology of the island and its sheltered lagoon. In Lesbos, Aristotle married Pythias, either Hermias’s adoptive daughter or niece. She bore him a daughter, whom they also named Pythias.

In Macedonian

In 343 BC, Aristotle was invited by Philip II of Macedon to become the tutor to his son Alexander. Aristotle was appointed as the head of the royal academy of Macedon. During Aristotle’s time in the Macedonian court, he gave lessons not only to Alexander, but also to two other future kings: Ptolemy and Cassander. Aristotle encouraged Alexander toward eastern conquest and Aristotle’s own attitude towards Persia was unabashedly ethnocentric. In one famous example, he counsels Alexander to be “a leader to the Greeks and a despot to the barbarians, to look after the former as after friends and relatives, and to deal with the latter as with beasts or plants”.

The Lyceum

By 335 BC, Aristotle had returned to Athens, establishing his own school there known as the Lyceum. Aristotle conducted courses at the school for the next twelve years. While in Athens, his wife Pythias died and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis of Stagira, who bore him a son whom he named after his father, Nicomachus.

By 335 BC, Aristotle had returned to Athens, establishing his own school there known as the Lyceum. Aristotle conducted courses at the school for the next twelve years. While in Athens, his wife Pythias died and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis of Stagira, who bore him a son whom he named after his father, Nicomachus.

This period in Athens, between 335 and 323 BC, is when Aristotle is believed to have composed many of his works. He wrote many dialogues, of which only fragments have survived. Those works that have survived are in treatise form and were not, for the most part, intended for widespread publication; they are generally thought to be lecture aids for his students. His most important treatises include Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, On the Soul and Poetics. Aristotle studied and made significant contributions to “logic, metaphysics, mathematics, physics, biology, botany, ethics, politics, agriculture, medicine, dance and theatre.”

His Death

Near the end of his life, Alexander and Aristotle became estranged over Alexander’s relationship with Persia and Persians. A widespread tradition in antiquity suspected Aristotle of playing a role in Alexander’s death, but the only evidence of this is an unlikely claim made some six years after the death. Following Alexander’s death, anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens was rekindled.

In 322 BC, Demophilus and Eurymedon the Hierophant reportedly denounced Aristotle for impiety, prompting him to flee to his mother’s family estate in Chalcis, on Euboea. He was said to have stated: “I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy”– a reference to Athens’s trial and execution of Socrates. He died on Euboea of natural causes later that same year, having named his student Antipater as his chief executor and leaving a will in which he asked to be buried next to his wife.

His work

His writings cover many subjects – including physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theatre, music, rhetoric, psychology, linguistics, economics, politics and government. Aristotle provided a complex synthesis of the various philosophies existing prior to him. As a result, his philosophy has exerted a unique influence on almost every form of knowledge in the West and it continues to be a subject of contemporary philosophical discussion.

Works

- The asterisk (*) denotes that these works are considered spurious.

Logical writings

- Categories (Owen) (trans. O. F. Owen) (1853)

- On Interpretation (trans. O. F. Owen) (1853)

- Prior Analytics (trans. O. F. Owen) (1853)

- Posterior Analytics (Owen) (trans. O. F. Owen)

- Topics (trans. O. F. Owen) (1853)

- The Sophistical Elenchi (trans. O. F. Owen) (1853)

Physical and scientific writings

- Physics (Aristotle) (or Physica)

- On the Heavens (or De Caelo)

- On Generation and Corruption (or De Generatione et Corruptione)

- Meteorology (or Meteorologica)

- On the Cosmos (or De Mundo, or On the Universe)

- Parva Naturalia or Little Physical Treatises is a collective term for the following seven works rather than a work in its own right.

- On Sense and the Sensible (trans. J. I. Beare) (1908))

- On Memory and Reminiscence (trans. J. I. Beare) (1908)

- On Sleep and Sleeplessness (trans. J. I. Beare) (1908)

- On Dreams (trans. J. I. Beare) (1908)

- On Prophesying by Dreams (trans. J. I. Beare) (1908)

- On Longevity and Shortness of Life (trans. G. R. T. Ross) (1908)

- On Youth and Old Age, On Breathing and On Life and Death

- On Youth and Old Age (or De Juventute et Senectute)

- On Life and Death (or De Vita et Morte)

- On Breathing (or De Respiratione)

- On Breath (or De Spiritu) *

- History of Animals (trans. D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson) (1910)

- On the Parts of Animals (trans. William Ogle) (1912)

- On the Movement of Animals (trans. A. S. L. Farquharson) (1912)

- On the Progression of Animals (trans. A. S. L. Farquharson) (1912)

- On the Generation of Animals (trans. Arthur Platt) (1912)

- Opusculum (Little works)

- On Colours (or De Coloribus) *

- On Things Heard (or De audibilibus) *

- Physiognomics (or Physiognomonica) *

- On Plants (trans. E. S. Forster) (1913) *

- On Marvellous Things Heard (or Mirabilibus Auscultationibus, or On Things Heard) *

- Mechanical Problems (or Mechanica) *

- On Indivisible Lines (or De Lineis Insecabilibus) *

- Situations and Names of Winds (or Ventorum Situs) *

- On Melissus, Xenophanes and Gorgias (or MXG) * (The section On Xenophanes starts at 977a13, the section On Gorgias starts at 979a11.)

- Problems (or Problemata) *

Metaphysical writings

- Metaphysics (trans. W. D. Ross) (1908) (or Metaphysica)

Ethical writings

- Nicomachean Ethics (or Ethica Nicomachea, or The Ethics)

- Great Ethics (or Magna Moralia) *

- Eudemian Ethics (trans. Joseph Solomon) (1915)

(or Ethica Eudemia)

(or Ethica Eudemia) - Virtues and Vices (or De Virtutibus et Vitiis Libellus, Libellus de virtutibus) *

- Politics (or Politica)

- Economics (or Oeconomica) *

Aesthetic writings

- Rhetoric (or Ars Rhetorica, or The Art of Rhetoric or Treatise on Rhetoric)

- Rhetoric to Alexander (or Rhetorica ad Alexandrum)*

- The Poetics (or Ars Poetica)

Works outside the Corpus Aristotelicum

- The Constitution of the Athenians (trans. Fredrick G. Kenyon) (1921)

His influence

Along with his teacher Plato, he is considered the “Father of Western Philosophy”. Aristotle’s views on physical science profoundly shaped medieval scholarship. Their influence extended from Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages into the Renaissance. Some of Aristotle’s zoological observations found in his biology, such as on the hectocotyl (reproductive) arm of the octopus, were disbelieved until the 19th century. His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, studied by medieval scholars such as Peter Abelard and John Buridan. Aristotle’s influence on logic also continued well into the 19th century.

Along with his teacher Plato, he is considered the “Father of Western Philosophy”. Aristotle’s views on physical science profoundly shaped medieval scholarship. Their influence extended from Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages into the Renaissance. Some of Aristotle’s zoological observations found in his biology, such as on the hectocotyl (reproductive) arm of the octopus, were disbelieved until the 19th century. His works contain the earliest known formal study of logic, studied by medieval scholars such as Peter Abelard and John Buridan. Aristotle’s influence on logic also continued well into the 19th century.

He influenced Islamic thought during the Middle Ages, as well as Christian theology. Aristotle was revered among medieval Muslim scholars as “The First Teacher”. And among medieval Christians like Thomas Aquinas as simply “The Philosopher”. His ethics, though always influential, gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics, such as in the thinking of Alasdair MacIntyre and Philippa Foot.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Author:Aristotle